How can I help my child with eating at home? Here are some helpful tips from Marsh Dunn Klein’s responsive feeding training

Feeding a child from the first days of their life can be a beautiful journey of mutual discovery for both the carer and the child. It can be, but it does not have to be. Today, I invite you to read an article in which we will pay more attention to the difficulties that may arise during feeding and the methods worth introducing to build a good relationship with food. The period of shaping healthy habits for a child is a time full of challenges.

Assisting children in the early days of introducing solid foods or in the following months when they already have the skills for independent eating, carers can display various attitudes towards accepting the child’s pace of eating (including their exploration). Carers can help developmentally, among other things, through shared meals (modelling behaviours, imitation), safely serving food (minimising the risk of choking), or being present during meals (a sense of closeness and security). A different attitude that the child may resist as a form of pressure can be associated with limiting help. For example, we can observe feeding dictated by haste, the caregiver’s reluctance to get the child/table dirty, sneaking in foods for the child to eat more, or, in the adult’s opinion, more varied eating or feeding while the child is asleep to ensure they have a “nutritious meal.”

As we can see, helping a child with eating can be either developmental or limiting; much depends on us adults and recognising the child’s readiness for the offered changes.

I like to reinforce among parents and carers the belief that “introducing solid foods is discovering its uniqueness throughout life.” It is a journey through tastes, textures, combinations, smells, and shapes. We need to be ready for the fact that children imitate us at first and, at the same time, learn to interpret the signals that children communicate to us.

When children do not eat as the adults would like, they also worry in a childish way. Often, adults don’t know how a child should eat, let alone a child we impose increasing demands on. Children may not eat for various reasons. As selected examples, we can mention medical issues (undiscovered food allergies, gastrointestinal diseases, other diet-related illnesses), physical issues (cavities, gum inflammations, short frenulum), past traumatic experiences, hospitalisation, or sensory processing issues. When a concerned caregiver, faced with their child not eating or including entire food groups in meals, doesn’t get support and doesn’t find peace, understanding, or the correct diagnosis, their concern can affect the child’s attitude towards eating. The higher the pressure, the expectation that the child will “finally start eating,” and the opposite effect may occur.

Source: Poradnik żywienia dziecka, Instytut Matki i Dziecka, Zakład Żywienia, Warszawa 2020

In the publications of Marsy Dunn Klein, we read that the first step towards a shared meal is calmness. How to build calmness around a meal? First, it’s worth asking yourself what this meal means to you. And then start again. Inviting a child to the table involves joint shopping, helping in the kitchen, the first independent cutting of shapes from pancakes, offering fruit to household members, and vegetables – squeezed juice. This is not yet a child’s meal. It’s their presence and co-creation of the atmosphere. It’s an opportunity for experiencing, smelling, touching, and also playing.

When introducing new foods or products into a child’s diet that requires more time, pay attention to the individual stages of this journey. The place, time, and invitation to the table, on the table safe, acceptable and new products that can be observed, offered to household members. You can talk about texture, compare colours, and look for differences and similarities. As an exciting method, Masha suggests the “s-t-r-e-t-c-h-i-n-g” method, which involves gradually introducing changes in one element: colour (adding colour from beets, spinach, cocoa), texture (dry pancake, buttery, with powder), shape (using cutters, cookie forms). Many foods can be “s-t-r-e-t-c-h-e-d,” including soups (changing additives, density), muffins (shapes, colours, forms), or fries (shapes).

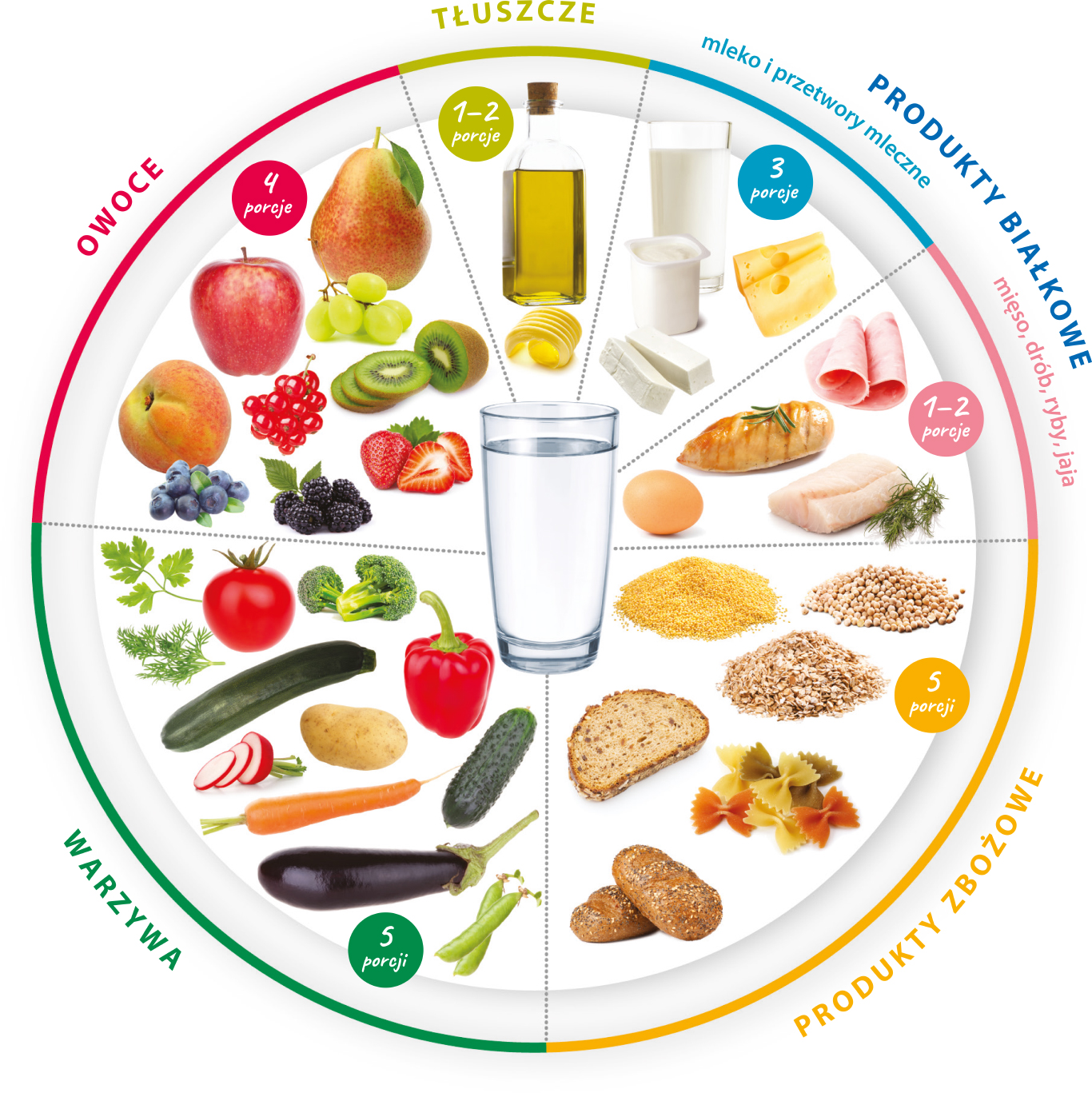

Nurseries and preschools that your children attend, apart from the obligation to serve healthy meals as part of implemented menus that must adhere to principles included, among others, in the healthy nutrition plate or the former children’s nutrition pyramid, should provide an opportunity to explore food during activities or children’s culinary activities.

Writing this article for you, I wanted to encourage you to take a new look at your shared meal. If you notice difficulties, trust your feelings and observations of your meals, and seek support that will restore peace to you and build a good relationship with food.

Masha Dunn Klein, the author of the book published by “Pestka i Ogryzek” Publishing House M. Baj-Lieder, R. Ulman-Bogusławska’ Anxious Eaters, Anxious Mealtimes: Practical and Compassionate Strategies for Mealtime Peace’.

Let’s meet!

We invite all of you to an individual meeting with the headteacher. This will be a great opportunity to find out about our educational offer, ask questions, and visit the kindergarten. You can book one visit for a given day.